Have you ever wondered why some friends never leave the house without sunglasses while others seem unfazed by bright sunlight? Part of the answer may be hidden in their eyes. Eye color isn’t just a cosmetic trait — it reflects the amount of melanin in your iris, which helps control how much light enters the eye. People with different eye colors often experience light and glare in distinct ways. In this article, we’ll dive into the science of eye color, explain why certain eye colors are more sensitive to light, and share tips for keeping your eyes comfortable and healthy.

The Science Behind Eye Color

Melanin: The pigment that shapes eye color

Eye color is determined by the concentration and distribution of melanin in the iris. Melanin is the same pigment that colors our skin and hair. According to MedlinePlus (a service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine), people with brown eyes have a large amount of melanin in the iris, while people with blue eyes have much less. The specific hue results from variations in genes related to melanin production, transport and storage.

The OCA2 and HERC2 genes on chromosome 15 play major roles. The OCA2 gene produces a protein involved in melanosome maturation, and variations in this gene decrease the amount of functional protein, reducing melanin and leading to lighter-colored eyes. A region in the HERC2 gene controls OCA2 expression, and certain polymorphisms reduce the P protein further. Other genes, like TYR and TYRP1, also influence pigment synthesis.

Eye color categories and melanin levels

While eye colors exist on a continuum, they’re often grouped into categories based on melanin levels:

- Brown eyes: High melanin levels and dense melanosomes. Brown is the most common eye color worldwide.

- Hazel and green eyes: Medium melanin levels and variable distribution. These eyes often combine brown pigment with green or yellow undertones.

- Blue and gray eyes: Low melanin levels and fewer melanosomes. The blue hue comes from light scattering in the iris stroma when little pigment is present.

- Amber eyes: A mix of melanin types, including higher amounts of pheomelanin (a red-yellow pigment).

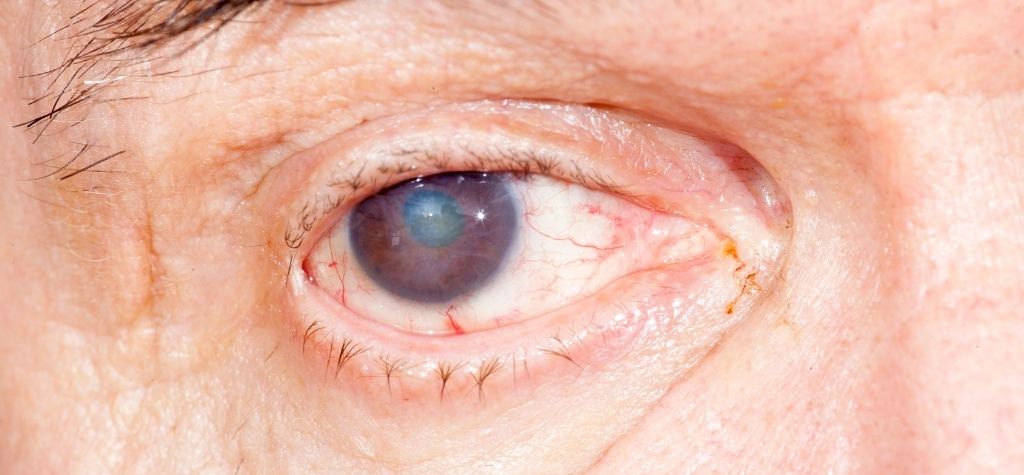

- Albinism or very light eyes: Minimal melanin due to genetic conditions like ocular albinism or oculocutaneous albinism, leading to severe light sensitivity.

Understanding melanin distribution sets the stage for why people with certain eye colors perceive light differently.

How Melanin Filters Light

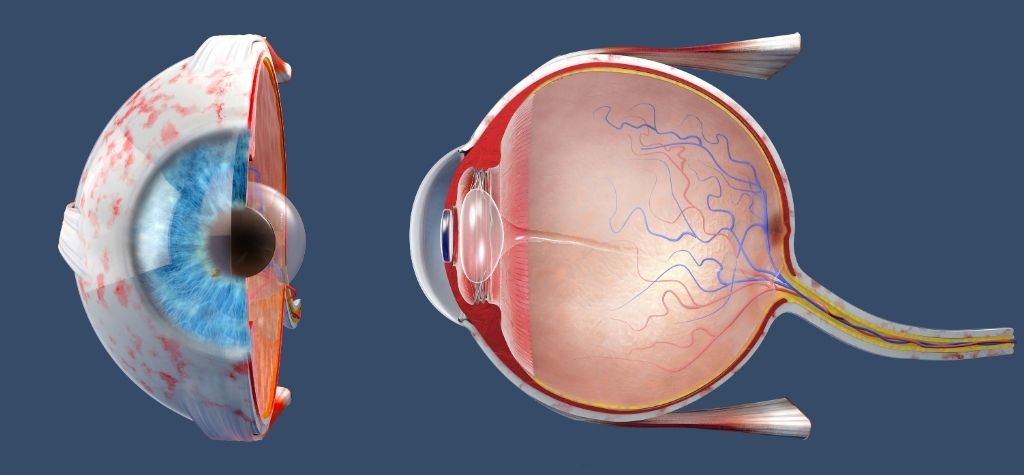

Protecting the retina from excess light

The iris controls the size of the pupil, but the pigment within the iris also filters incoming light. The International Journal of Ophthalmology review on iris color and eye diseases explains that darkly pigmented individuals have more melanin in their eyes, which protects the retina from excessive sunlight exposure and reduces oxidative damage. In other words, melanin acts like a built‑in pair of sunglasses.

People with dark brown eyes have more eumelanin and a higher number of melanosomes, providing better absorption of ultraviolet (UV) and high‑energy visible light. Meanwhile, blue eyes have similar numbers of melanocytes but contain less pigment and fewer melanosomes. Green or hazel eyes fall somewhere in between. Less pigment means more light passes through the iris and reaches the back of the eye.

Differences in light sensitivity

Because melanin absorbs and scatters light, individuals with lighter eyes often experience more glare and discomfort in bright conditions. The review notes that dark-eyed people’s melanin protects against excessive sunlight, reducing oxidative damage, while lighter eyes transmit more light to the retina. This difference may explain why your light-eyed friends squint in bright sunshine and often reach for sunglasses.

Corneal and Neurological Sensitivity

Corneal sensitivity varies with iris pigmentation

Light sensitivity isn’t only about the iris. The cornea, the clear front surface of the eye, is also sensitive to temperature and touch. A Review of Optometry news report found that as iris pigmentation decreases, corneal sensitivity increases. Researchers measured corneal sensitivity in subjects using a noncontact esthesiometer and ranked iris color from blue (grade 1) to very dark brown (grade 5). They observed that blue-eyed participants tended to have more sensitive corneas than those with brown eyes.

The authors speculated that the melanin in the iris may correlate with neuromelanin levels in the central nervous system. This could mean that differences in neural pathways influence how the brain processes light and touch sensations in the cornea.

Intraocular stray light and contrast

Although not directly cited here, other research suggests that light-colored eyes may experience more intraocular stray light—light that scatters within the eye and reduces contrast. Higher stray light can cause glare, making it harder to see clearly in bright environments. Darker eyes, with more pigment, scatter less stray light and may handle glare better. However, stray light measurements vary widely among individuals and depend on factors beyond iris color, such as lens clarity and age.

Disease Risks Linked to Eye Color

Eye color doesn’t determine whether you’ll develop an eye disease, but it can influence risk factors. Melanin’s protective role extends beyond glare control.

Cataracts and pigmentation

Cross‑sectional studies summarized in the epidemiologic review show that darker iris color is associated with a higher risk of age‑related cataracts. Nuclear cataracts involve cloudiness in the central lens and may develop more often in brown-eyed individuals. The exact reasons are unclear, but high melanin concentrations might lead to increased heat absorption or other metabolic changes in the lens.

Age‑related macular degeneration (AMD)

The relationship between eye color and AMD isn’t consistent. Some studies show light-colored irises may be associated with greater progression of AMD, possibly because less melanin allows more blue light and UV radiation to reach the retina. However, other studies found no significant association. Because AMD has many genetic and environmental contributors, eye color is considered a minor factor.

Uveal melanoma

Uveal melanoma is a rare but serious eye cancer affecting the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body and choroid). The review notes that light iris color has been shown to be the most consistent risk factor for uveal melanoma, with studies reporting higher incidence among people with blue or grey eyes. Researchers propose that less melanin in choroidal melanocytes offers less protection against UV radiation. For individuals with light eyes, wearing UV‑protective sunglasses and hats is especially important.

Photophobia in albinism and heterochromia

Genetic conditions that drastically reduce melanin, such as ocular albinism and oculocutaneous albinism, often cause severe photophobia. Patients may have pale irides, poor visual acuity, and nystagmus (involuntary eye movement). Heterochromia, where each eye is a different color, is usually benign but can be a sign of injury or genetic conditions. Because one eye may be lighter, people with heterochromia sometimes notice that their lighter eye feels more sensitive in bright light than the darker eye.

Genetic and Environmental Interactions

Gene–environment interaction

Eye color comes from genes, but sunlight exposure and lifestyle can influence how those genes express. The epidemiologic review mentions that a synergistic effect exists between light iris color and UV radiation exposure: people with light eyes may have an especially increased risk of uveal melanoma when they are exposed to high UV levels. This suggests that environmental factors like sunlight amplify the impact of lighter eye color.

Age‑related changes in pigmentation

Studies suggest that the human iris may become lighter with increasing age, potentially due to changes in melanosome morphology. This could mean that light sensitivity might increase as people get older, even if their eye color doesn’t noticeably change. Aging also reduces pupil size and lens transparency, affecting light perception for everyone regardless of eye color.

Eye color and drug response

The Review of Ophthalmology notes that patients with deep brown irides have two to four times more ocular melanin than those with light blue eyes. Melanin can bind to medications, altering how drugs are absorbed and released in the eye. While this doesn’t directly affect light sensitivity, it highlights another way that eye pigmentation can impact ocular health. For example, prostaglandin analogs used for glaucoma can cause iris darkening as a side effect.

Do Eye Colors Affect Night Vision and Color Perception?

Many people wonder if light-eyed individuals see better at night or if dark-eyed individuals perceive colors more vividly. Scientific evidence is limited. Some small studies suggest that blue-eyed individuals may have slightly higher intraocular stray light, which could affect contrast and glare but might also enhance perception in dim environments. However, these differences are subtle and easily outweighed by factors like age, overall eye health and refractive error.

Color perception depends on the retina’s cone cells, which are the same regardless of iris color. Therefore, eye color does not significantly influence the ability to distinguish colors. Differences you may notice between friends are more likely due to lighting conditions, individual variability or the presence of eye conditions such as cataracts or macular degeneration.

Practical Tips for Managing Light Sensitivity

No matter what color your eyes are, protecting them from excessive light helps maintain comfort and long-term health. Here are some strategies:

- Wear UV-protective sunglasses. Look for sunglasses that block 100 % of UVA and UVB rays. Wraparound styles provide additional protection for light-eyed individuals who may be more sensitive to glare. Polarized lenses reduce reflected light from surfaces like water and snow.

- Use broad-brimmed hats or visors. A hat blocks overhead sunlight and reduces the amount of light entering from above.

- Adjust indoor lighting. If fluorescent lights bother you, opt for softer LED bulbs and position them so they don’t shine directly into your eyes. Anti-glare screens can make computer use more comfortable.

- Consider photochromic or tinted lenses. Photochromic lenses darken in response to UV light, making them ideal for people who move between indoor and outdoor environments. Mild tints can reduce glare indoors.

- Regular eye exams. Early detection of cataracts, glaucoma or macular degeneration is essential, regardless of eye color. Tell your eye doctor if you experience excessive light sensitivity, as it could signal underlying issues.

- Diet and lifestyle. A diet rich in antioxidants like lutein and zeaxanthin (found in leafy greens) may help protect the retina. Not smoking and controlling blood pressure also reduce the risk of eye diseases.

Conclusion and Takeaway

Eye color is more than a beautiful trait; it’s a window into how your eyes interact with light. Melanin in the iris determines whether your eyes are better at filtering bright sunlight or more prone to glare. Brown eyes, with their abundance of melanin and melanosomes, tend to resist UV damage and reduce stray light, though they may carry a slightly higher risk of cataracts. Blue and green eyes contain less pigment, making them more sensitive to bright light and potentially more vulnerable to conditions like uveal melanoma.

Corneal sensitivity also plays a part: research shows that lighter eyes may have more sensitive corneas, which can translate into discomfort under strong light. Genetic factors such as OCA2 and HERC2 control melanin production and can result in very light eyes or conditions like albinism. Environmental factors like UV exposure interact with eye color to influence disease risk.

Remember, eye color is just one piece of the puzzle. Eye health depends on regular check-ups, protective habits and a nutrient-rich diet. If bright light bothers you, talk to an eye care professional about tailored solutions, whether that means polarized sunglasses, tinted lenses or simply carrying a hat on sunny days. By understanding how melanin and genetics influence your eyes, you can make informed decisions to keep your vision comfortable and clear for years to come.