Have you ever wondered if there’s a way to nudge your eyes into staying healthy or even restore some lost vision? Researchers are increasingly looking to peptides—small chains of amino acids that act as messengers in the body—for answers. While peptides have gained fame in bodybuilding and skin‑care circles, scientists are also exploring them as tools to protect photoreceptors, heal corneas, calm inflammation and even regenerate optic nerves. This article explains what peptides are, how they might affect your eyes, the evidence behind current research and why cautious optimism (rather than hype) is warranted.

What Are Peptides?

Peptides are short sequences of amino acids—the building blocks of proteins. Unlike large proteins, peptides are small enough to interact with cell receptors directly. In the body they work as hormones, growth factors, neurotransmitters and signalling molecules. Because of their size and specificity, peptides can trigger targeted biological responses without some of the widespread side‑effects associated with other drugs.

When we talk about peptides for eye health, we typically mean synthetic fragments of naturally occurring proteins that researchers hope will mimic the protective or regenerative functions of the full protein. For instance, the retina naturally produces pigment epithelium‑derived factor (PEDF), which helps keep photoreceptors alive. Scientists have created small PEDF‑derived peptides that may deliver similar protective signals while being small enough to penetrate ocular tissues.

Key Mechanisms of Peptides in the Eye

Peptides under investigation for eye health fall into a few broad categories:

- Photoreceptor protection: Some peptides shield light‑sensing cells from degeneration. PEDF‑derived peptides are designed for this purpose.

- Tissue repair: Collagen mimetic peptides bind to damaged collagen, helping restore stiffness and structure in ocular tissues such as the sclera and optic nerve head. Others, like BPC‑157, accelerate corneal wound healing.

- Inflammation control: Bioactive peptides like DFCPPGFNTK (from fish skin) can reduce oxidative stress and inflammation on the ocular surface, easing dry‑eye symptoms.

- Neuroprotection and regeneration: Neurotrophic peptides such as Semax support optic nerve health and may improve visual field parameters, while experimental fibronectin‑derived peptides stimulate optic nerve regrowth in animals.

Before diving into these categories, it’s important to remember that most peptide therapies for the eye are experimental. Very few are approved for human use, and many studies are still in early stages with animals or cell cultures. Always consult an eye‑care professional before considering any peptide treatment.

Peptide Eye Drops for Retinal Diseases

PEDF‑derived peptides: protecting photoreceptors

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) and age‑related macular degeneration (AMD) are conditions where light‑sensing photoreceptor cells gradually die. Because these diseases involve mutations in hundreds of different genes, developing targeted drugs is challenging. Researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) have focused on pigment epithelium‑derived factor (PEDF), a protein naturally produced in the eye that protects photoreceptors. The problem: the full protein is too large to reach the retina when delivered as eye drops.

To solve this, the NEI team created small peptide fragments of PEDF. In a 2025 study they applied eye drops containing these peptides to mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa. Remarkably, the peptides reached the retina within one hour and daily treatment slowed the loss of light‑sensitive cells and vision in the mice. The researchers also tested the peptides on human retinal organoids (lab‑grown retina‑like tissues) exposed to cigarette smoke extract. The peptides kept many more photoreceptor cells alive compared with untreated samples. These findings offer proof of concept that PEDF‑derived peptides could protect retinas from genetic diseases or age‑related damage.

A separate article reporting the same research described the approach more simply: the team designed small peptides that are “small enough to move through eye tissue” and found that the drops could slow the loss of photoreceptor cells in multiple mouse models of RP. Importantly, the treatment isn’t a cure but could delay disease progression while patients await gene therapies.

How these peptides work

PEDF works by binding to receptors on photoreceptor cells and triggering anti‑inflammatory and anti‑apoptotic pathways. The small peptides mimic the key region of PEDF responsible for this activity. Research shows that when applied as eye drops, these peptides can cross the cornea and reach the retina. In mouse experiments, PEDF‑derived peptides decreased pro‑apoptotic markers like the BAX/BCL2 ratio and improved photoreceptor survival. That means they may help cells resist the death signals that drive RP and AMD.

Collagen Mimetic Peptides: Supporting Eye Structure

Before moving on, it’s worth pointing to a few external resources for those interested in learning more. The NEI offers an overview of the causes and symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa: Retinitis Pigmentosa. The NIH Research Matters article “Peptide eye drops may help protect vision” summarizes the PEDF peptide study discussed above, and the open‑access Communications Medicine paper “H105A peptide eye drops promote photoreceptor survival” provides technical details of the research.

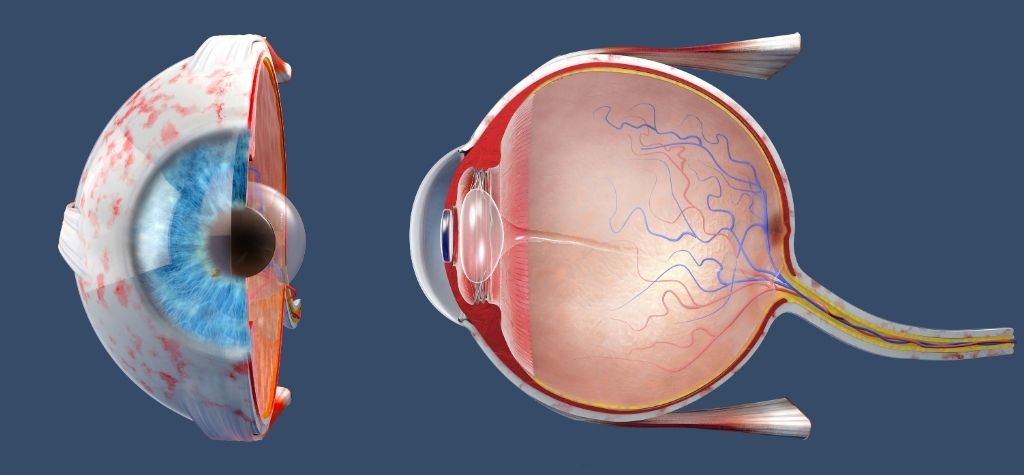

Why collagen matters for vision

The eye’s sclera (white outer layer) and the optic nerve head (where retinal nerve fibers exit the eye) are rich in collagen. Collagen gives these tissues strength and stiffness to withstand intra‑ocular pressure. When collagen breaks down or becomes disorganized—due to aging, myopia, glaucoma or inflammation—the tissues soften. This can lead to deformation of the eyeball (as in myopia), compromised support for optic nerve fibers, and greater susceptibility to damage.

Researchers have developed collagen mimetic peptides (CMPs)—short single‑stranded peptides that selectively bind to damaged collagen triple helices. By attaching to frayed collagen fibers, CMPs act as “molecular bandages” that help restore the integrity of the extracellular matrix.

Evidence from animal studies

A 2025 study used atomic force microscopy to measure how elevated intra‑ocular pressure softens the peripapillary sclera and glial lamina in rats. Four weeks of raised pressure reduced tissue stiffness and increased fragmented collagen. When scientists applied a collagen mimetic peptide topically during this period, it countered the pressure‑induced softening, suggesting the peptide repaired damaged collagen. The authors concluded that topical CMPs could mitigate changes in scleral and optic nerve head stiffness in conditions like myopia and glaucoma.

Another experiment examined the ability of CMPs to repair collagen damaged by the enzyme MMP‑1, which is involved in many eye diseases. Researchers treated sections of rat optic nerve head with MMP‑1 to degrade collagen and then applied a collagen mimetic peptide. The MMP‑1 dramatically reduced tissue stiffness, but CMP treatment partially restored the stiffness and reduced collagen fragmentation. This study suggests CMPs could help maintain biomechanical integrity of the sclera and optic nerve head, potentially slowing structural changes that lead to vision loss.

For readers who want to explore the primary literature, the findings discussed here come from two open‑access MDPI publications. One describes how topical application of a collagen mimetic peptide restored scleral stiffness in rats subjected to elevated ocular pressure: “Topical Application of a Collagen Mimetic Peptide Restores Peripapillary Scleral Stiffness”. The other details how a collagen mimetic peptide repaired MMP‑1‑damaged collagen in the rodent optic nerve head: “Collagen Mimetic Peptides Promote Repair of MMP‑1‑Damaged Collagen in the Rodent Sclera and Optic Nerve Head”.

Myopia and glaucoma implications

The sclera’s mechanical properties influence how the eye grows and responds to intra‑ocular pressure. Scleral thinning and loss of stiffness are linked to axial elongation in myopia, while altered collagen architecture in the peripapillary sclera is implicated in glaucoma. By restoring collagen stiffness, CMPs might theoretically slow the progression of high myopia or bolster the optic nerve’s resilience to pressure in glaucoma. However, these applications remain speculative; human trials are needed.

Peptides for Corneal Healing and Dry‑Eye Relief

BPC‑157: accelerating corneal repair

Corneal wounds—whether from trauma or surgery—must heal quickly to maintain transparency and prevent infection. In a 2015 rat study, researchers tested BPC‑157, a 15‑amino‑acid peptide originally derived from gastric juice, for its ability to heal corneal injuries. They made a small incision in the cornea and applied eye drops containing various doses of BPC‑157. Compared with control animals, the BPC‑157‑treated rats showed faster healing: fluorescein dye tests became negative sooner, and epithelial defects closed completely by 72 to 96 hours, depending on dose. BPC‑157 also prevented the growth of unwanted blood vessels into the injured area, helping preserve corneal transparency. These results suggest BPC‑157 eye drops could one day be used to speed recovery after corneal surgery or injury.

The findings summarized here come from an Experimental Eye Research study on rats. You can read the abstract of that study on PubMed: “Perforating corneal injury in rat and pentadecapeptide BPC 157”.

While the study is promising, it is important to note that BPC‑157 is not approved for any ophthalmic use. Many of the claims surrounding BPC‑157 originate from animal studies, and its long‑term safety in humans is not established.

Fish‑derived peptide DFCPPGFNTK for dry eye

Dry‑eye disease affects millions of people and involves a vicious cycle of tear film instability, inflammation and cell death. Standard treatments like artificial tears provide only temporary relief. Scientists in China identified a 10‑amino‑acid peptide (DFCPPGFNTK) from tilapia skin hydrolysate that may offer a new approach. In laboratory experiments, high salt concentrations harmed human corneal epithelial cells, reducing viability and upsetting mitochondrial function. Applying the DFC peptide improved cell viability and mitochondrial membrane potential. In a mouse model of dry eye induced by benzalkonium chloride (a preservative), the peptide improved tear production, prevented thinning of the corneal epithelium, reduced loss of conjunctival goblet cells and decreased cell apoptosis.

Dry eye is driven by oxidative stress and inflammation. The study showed that DFC reduced reactive oxygen species, increased antioxidant enzyme activity and lowered markers of oxidative damage. It also decreased pro‑inflammatory signalling, reducing levels of IL‑6, TNF‑α and COX‑2. The authors concluded that DFC alleviates dry eye by suppressing oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis and autophagy. Again, this work is pre‑clinical; human studies will be needed to confirm benefits and safety.

Other peptides in corneal and ocular surface repair

Research into peptides for ocular surface healing is diverse. Collagen mimetic peptides not only strengthen the sclera but also promote corneal epithelial healing and restore corneal nerve beds after injury, according to animal studies. Histatin‑derived peptides (naturally found in saliva) are being investigated for their ability to improve ocular surface health in dry‑eye models. Calcitonin gene‑related peptide (CGRP) has been found to protect corneal nerves and modulate inflammation in experimental settings. However, most of these peptides remain in early research phases.

Neuroprotective Peptides for Optic Nerve Health

Semax: a neurotrophic peptide for optic nerve disease

Russia has long explored the therapeutic potential of Semax, a synthetic heptapeptide derived from adrenocorticotropic hormone. Semax acts as a nootropic and neuroprotective agent. In the early 2000s, clinicians tested Semax on patients with vascular, inflammatory and toxic diseases of the optic nerve. Participants received either intranasal drops or endonasal electrophoresis in addition to standard therapy. According to the study’s abstract, adding Semax accelerated recovery and improved visual functions: patients showed better visual acuity, wider visual fields, improved electric sensitivity and conductivity of the optic nerve, and improved color vision compared with controls. Semax was described as protecting nervous tissue from injury and shortening the acute phase of optic‑nerve disease.

The main findings above are drawn from a small Russian clinical trial. You can find the study abstract on PubMed: “Evaluation of therapeutic effect of Semax in optic nerve disease”.

Although promising, these findings come from small, early trials and mostly Russian‑language publications. Semax is not approved for optic‑nerve treatment in most countries. Its availability is limited, and further controlled studies are needed to confirm efficacy and safety.

Experimental peptides for optic nerve regeneration

Vision loss from optic nerve damage—whether from trauma or glaucoma—is considered irreversible because adult mammalian neurons rarely regrow. Recent experimental work suggests that peptides may help. In a 2024 research programme, scientists investigated fibronectin‑derived peptides—small fragments of a protein secreted during inflammation. In mice with crushed optic nerves, injections of these peptides stimulated dense regrowth through the injury site within six weeks and extended nerve fibers to the optic chiasm. The peptides improved survival of nerve cells and, when combined with gene therapy, enhanced regeneration even further. Researchers highlight that the peptides are just small pieces of protein, making them relatively simple to manufacture and deliver. Longer trials are ongoing to see if regenerated fibers can reconnect with brain centres for vision.

Again, this work is in animals. It illustrates a potential future where peptide injections could help repair optic nerve injuries. Until larger animal and human studies confirm these findings, such therapies remain speculative.

For a lay-friendly summary of this research, the University of Connecticut’s news site published an article titled “Nerve Regrowth in Sight” that explains how fibronectin-derived peptides helped regrow optic nerves in mice.

How Peptides Might Improve Eyesight: Mechanisms Explained

Although each peptide works differently, several general mechanisms explain how peptides could support eye health:

- Antioxidant activity: Many eye diseases involve oxidative damage. Peptides like DFC boost antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase and catalase) and reduce reactive oxygen species.

- Anti‑inflammatory effects: Chronic inflammation damages corneal and retinal cells. By decreasing pro‑inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF‑α, IL‑6) and enzymes (COX‑2, iNOS), peptides help protect tissues.

- Anti‑apoptotic signals: In degenerative diseases, cells often die through apoptosis. PEDF‑derived peptides decrease pro‑apoptotic markers, while DFC modulates Bcl‑2/Bax signalling to reduce cell death.

- Matrix repair: Collagen mimetic peptides bind to damaged collagen and restore stiffness in sclera and optic nerve head, supporting structural integrity.

- Neurotrophic stimulation: Peptides like Semax and fibronectin fragments may promote nerve survival and regrowth by enhancing growth factor pathways and cell adhesion.

- Wound healing: BPC‑157 accelerates corneal wound closure and prevents neovascularization.

These mechanisms are complex and sometimes overlap. For instance, reducing oxidative stress can also dampen inflammation and apoptosis, while improving matrix integrity may indirectly protect neurons.

Peptides in Eye‑Care Products: Separating Hype from Reality

The popularity of peptides in skin‑care has spawned a wave of creams and serums claiming to “brighten eyes” or “erase dark circles.” Most cosmetic eye‑cream peptides are signal peptides—small fragments that stimulate collagen production in the skin. Examples include palmitoyl pentapeptide‑4 (Matrixyl) and copper peptide GHK‑Cu, which help firm and smooth the delicate skin around the eyes. While these peptides improve skin texture, they do not directly improve vision.

Some high‑end cosmetics include topical copper peptides that may reduce inflammation and encourage wound healing. Copper peptides have been shown to stimulate collagen and elastin in skin, and they may support hair growth as well. However, cosmetic formulations are not designed to reach ocular tissues. Always avoid placing skin‑care products directly on the eyeball.

Safety, Regulation and Practical Considerations

Peptide therapies for eye health are promising but come with several caveats:

- Regulatory status: As of January 2026, no peptide eye drop is FDA‑approved for treating retinal diseases or optic nerve injuries. Some peptides (like PEDF fragments) are moving toward early human trials. Others, such as BPC‑157, are sold as research chemicals and not approved for human use.

- Safety unknowns: Most studies are short‑term and involve animals. Long‑term effects on human eyes are unknown. Peptides might alter immune responses, induce unwanted vessel growth or trigger allergic reactions.

- Doping and ethics: Peptides that raise growth hormone levels or act as growth factors are banned in competitive sports. Even peptides aimed at healing might fall under anti‑doping rules.

- Quality control: Because many peptide products are unregulated, purity and dosage can vary. Contaminants could cause infections or toxic reactions.

- Access through clinics: Some anti‑aging or regenerative medicine clinics offer peptide treatments off‑label. If you consider this route, consult a licensed ophthalmologist and verify that the peptide has undergone safety testing.

When to Consult a Doctor

You should see an eye‑care professional if you are considering any peptide therapy, especially if you have:

- Progressive retinal diseases (e.g., retinitis pigmentosa, age‑related macular degeneration);

- Chronic dry‑eye symptoms unresponsive to over‑the‑counter treatments;

- Corneal injuries or post‑surgery healing concerns;

- Optic nerve diseases or glaucoma requiring neuroprotective strategies.

An ophthalmologist can explain evidence‑based options, enrol you in clinical trials if appropriate and warn you about unproven products.

The Future of Peptide Therapies for Vision

The field of peptide therapeutics for eye health is rapidly evolving. Highlights include:

- Retinal preservation: PEDF‑derived peptides show strong pre‑clinical evidence for slowing photoreceptor loss in retinitis pigmentosa and possibly age‑related macular degeneration.

- Collagen repair: Collagen mimetic peptides offer a new strategy to maintain scleral and optic nerve head stiffness, potentially addressing underlying mechanics in myopia and glaucoma.

- Dry‑eye relief: Fish‑derived peptides like DFC reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, improving tear production and protecting corneal cells.

- Corneal healing: BPC‑157 speeds wound closure and preserves transparency in rat corneas.

- Neuroprotection and regeneration: Semax may improve visual field parameters in optic‑nerve diseases, and fibronectin‑derived peptides spur optic nerve regrowth in mice.

What remains to be seen is how these findings translate to humans. Clinical trials will need to establish optimal dosing, delivery methods, safety profiles and long‑term outcomes. In the meantime, maintaining eye health through proven measures—regular eye exams, balanced nutrition, UV protection, blood sugar control and avoiding smoking—remains critical.

Conclusion and Takeaway Messages

Peptide science offers a compelling glimpse into the future of eye care. By harnessing tiny fragments of proteins, researchers aim to protect photoreceptors, rebuild collagen scaffolds, soothe inflammation and even regrow nerve fibers. Animal and lab studies suggest that peptide eye drops or injections could one day slow or reverse certain causes of vision loss. However, these therapies are still in development.

To recap:

- Peptides are small but powerful: They can deliver targeted signals that modulate cell survival, inflammation and tissue repair.

- Evidence is mostly pre‑clinical: Most studies are in mice, rats or cell cultures. Human trials are just beginning.

- Safety first: Never self‑administer unapproved peptide products. Work with qualified eye‑care professionals and consider enrolment in clinical trials.

- Complement, don’t replace: Even if peptide therapies become available, they will likely complement—not replace—current treatments like anti‑VEGF injections for retinal diseases or standard dry‑eye therapies.

For now, peptides represent a promising but not yet proven avenue in vision science. With careful research and clinical oversight, they may one day broaden the toolbox for preventing and treating sight‑threatening conditions.